New Heritage and the Rise of the Science Functional

Thoughts on a talk by Bruce Sterling at SXSW 2025

I just attended a talk at SXSW by Bruce Sterling, and as usual, he delivered a deep, dense dive into big ideas. This time, it was about New Heritage, a concept that struck a chord with me. It sharpened something I’ve been thinking about, and professionally practicing, for a while—the way speculative ideas, once dismissed as fiction, can eventually become functional realities.

The above video was made in 2018 for a series of talks on using Sci-Fi as inspiration in the creative practice.

New Heritage and the Rise of the Science Functional

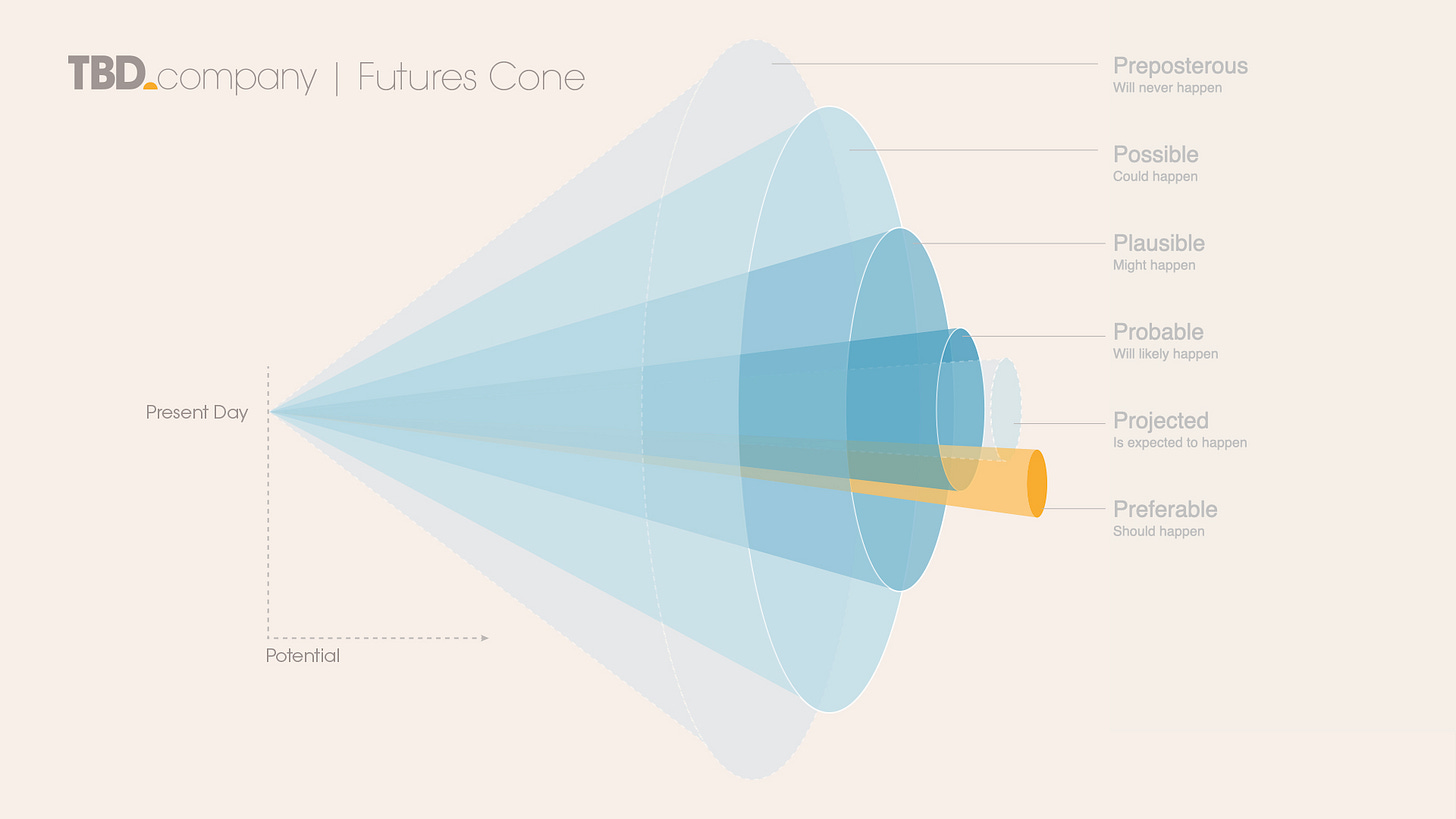

Some ideas arrive too soon. They show up before the tools exist to make them real, before the materials can support them, before anyone takes them seriously. They’re born as fiction, dismissed as fantasy, and left to linger in the margins of speculative thought. But time has a way of reshaping the impossible. What once seemed preposterous eventually becomes possible, and what’s possible—given enough time, ambition, and technological drift—often becomes probable. Even real.

This is the essence of New Heritage, the moment when an idea outlives its creator but finally gets realized. It’s the long arc of speculative thinking bending toward functionality, where yesterday’s fiction becomes today’s object of use. And it raises an interesting question: What happens to the legacy of visionaries whose ideas weren’t just ahead of their time, but outside of it?

From Science Fictional to Science Functional

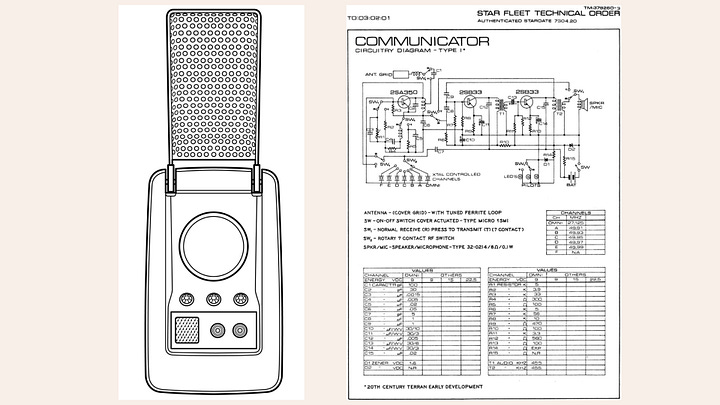

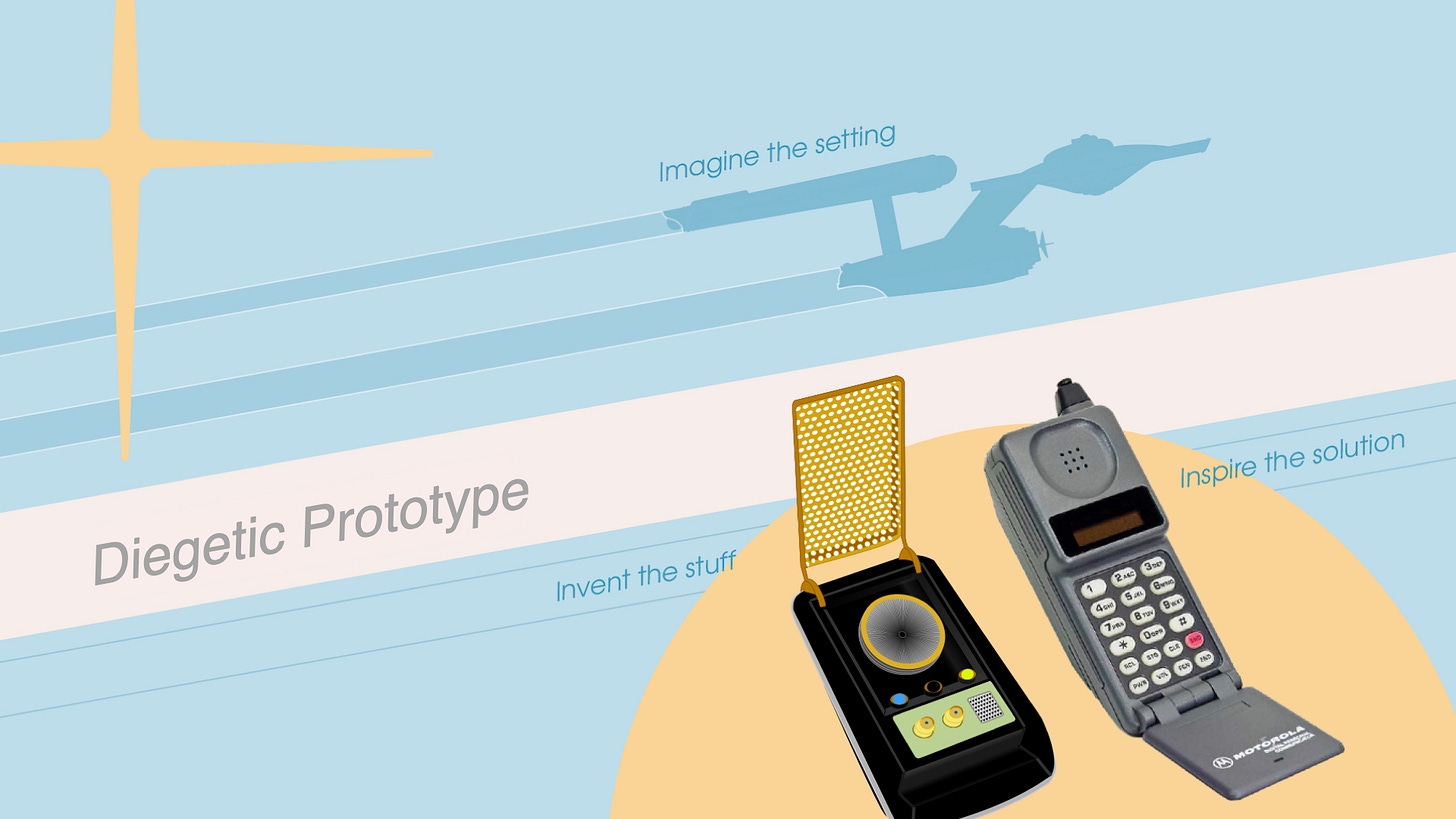

There’s a common phrase: science fiction becomes science fact. It’s neat, but it’s misleading. Science fiction is often concerned with metaphor, exaggeration, and social critique—it doesn’t exist to predict the future, even when it does by accident. But every so often, a concept imagined in fiction (a diegetic prototype) finds its way into reality, not as a direct translation, but as an echo. The Star Trek communicator didn’t lead directly to the flip phone, but the idea of a handheld, wireless communicator was lodged into the cultural imagination, waiting for the right moment.

That’s where the idea of Science Functional1 comes in. Unlike “science fiction,” which sketches possibilities without the burden of execution, something Science Functional has made the leap. It’s an object, a technology, or a system that was once speculative but now exists in a form that works. Not just a replica or a tribute, but something that functions in the real world, in a way that the original visionary could barely have imagined.

This transition is a kind of technological inheritance—a passing of the baton across decades or centuries. Jules Verne dreamed up a journey to the moon, but it was Wernher von Braun and NASA engineers who made it real. Leonardo da Vinci sketched flying machines, but it took the Wright brothers to leave the ground. In these moments, the original creator isn’t just a dreamer but an ancestor to something real.

When the Past Inherits the Future

Sterling touched on this in his talk at SXSW, exploring how old speculative designs can be revived and made functional. He and his team are building a working version of a fictional poetry-writing machine from a 1971 Italian sci-fi show. When the show aired, the idea was satirical—an absurd exaggeration of automation. But today, with AI-generated poetry just a few keystrokes away, the once-fictional machine is suddenly feasible.

It’s a strange reversal: instead of the future inheriting the past, the past is inheriting the future. Ideas that once existed only as jokes, metaphors, or artistic props are being pulled forward into real-world applications, sometimes long after their original creators have died. And this raises an interesting cultural dilemma: Who gets credit? If we make a working version of da Vinci’s flying machine today, is it his invention or ours? If someone builds a fully functional AI assistant modeled after HAL 9000, does that belong to Kubrick and Clarke, or to the engineers who made it real?

We’re used to the idea of technological innovation being forward-looking, always focused on the next big breakthrough. But New Heritage suggests that innovation is just as much about looking backward—digging up speculative artifacts from history and finally giving them form.

A New Role for Design Fiction

This shifts the conversation about design fiction. It’s often positioned as a way to prototype the future—producing speculative artifacts to make people think about what might come next. But what if it also has a role in reviving lost futures? What if design fiction isn’t just about provoking thought, but about reaching back and making things real that were once impossible?

Maybe Science Function is the missing link. It’s the moment when a speculative idea stops being just a concept and starts existing in the world, fully realized. It’s not just about replicating the aesthetics of the past or paying homage to an old vision—it’s about making something work.

And if that’s the case, then our role as designers, technologists, and speculative thinkers isn’t just to imagine new things. It’s to act as archivists of forgotten ideas, searching through the old, the improbable, and the discarded, and asking: Is it time yet?

Science Function & Science Functional are terms I coined while watching Bruce speak. Of course, the domains (.com) for both were already taken. So, while not entirely original play on words, I feel like it might be new to this community. If not, well, great minds, yada yada.

Super cool idea!! I think this gets even more interesting when we dont only talk about design fiction having this effect with technologies, but also with seeing beyond the current systems we live in, current ways of viewing the world, current subjectivities. We get so stuck in neoliberale ways of thinking, i believe speculative fiction, design fiction can be a big help in keeping our eyes and minds open to a better future.