Embracing the Apocalypse

Design Fiction in a World on the Brink

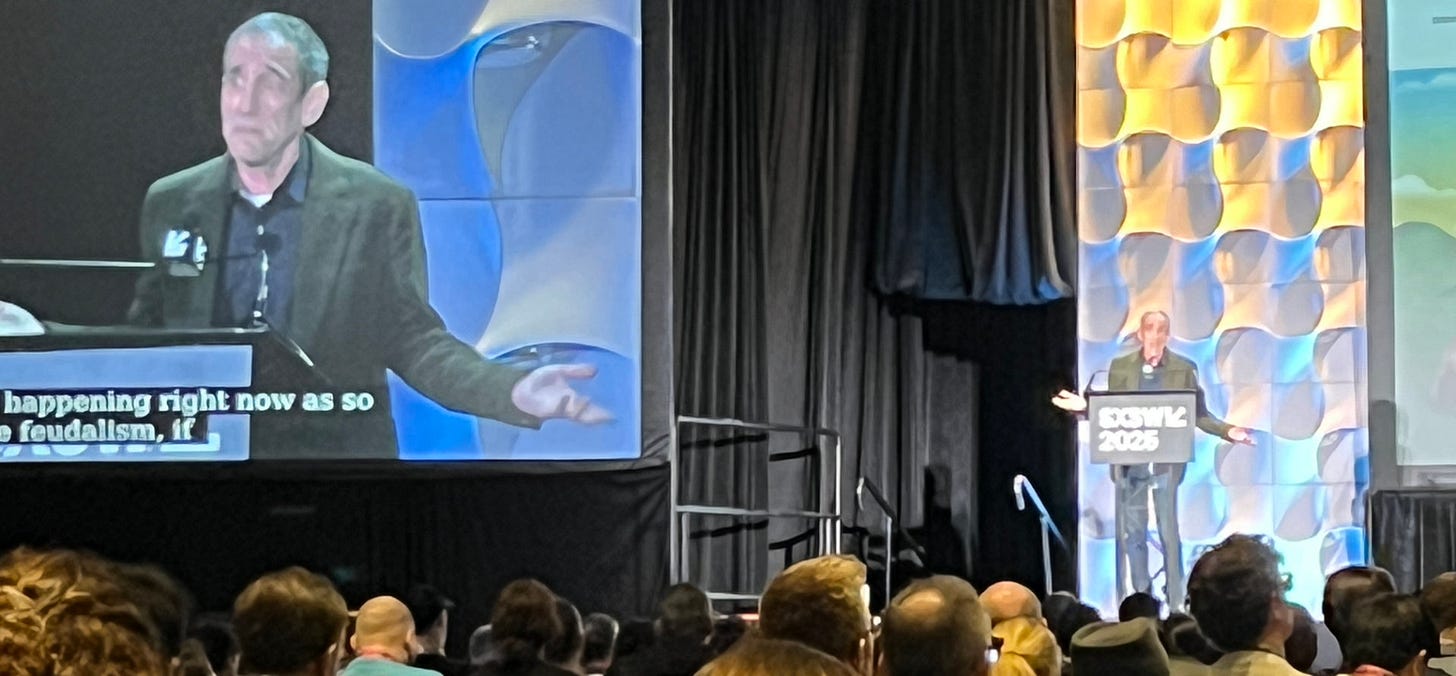

Douglas Rushkoff makes a compelling case that we should stop trying to predict the future and instead focus on creating it. His SXSW talk wasn’t just about economic collapse, billionaire paranoia, or the death spiral of infinite growth—it was about how we, the weirds1, still have agency. And this is where my interpretation of his ideas intersects with design fiction.

Design fiction is not about predicting the future; it’s about making it tangible. It’s about showing alternative possibilities, making them feel real enough to consider, even act upon. When Rushkoff talks about rejecting the dominant narrative—capitalism as an immutable force, the internet as a flattened influencer-driven monoculture, the billionaire class as our supposed architects of the future—he’s asking us to tell different stories. To rewrite reality. And what is design fiction if not an exercise in rewriting what we assume is fixed?

But let’s not overlook the real heart of Rushkoff’s argument: the weirds. The weirds have always been the ones to break through the homogeneity, to bring forth new rituals, new culture, new ways of being. Not the centralized forces of power, but the ones on the edges, the ones who refuse to be assimilated into the algorithmic average.

The mistake many make when thinking about the future is assuming it’s something we must adapt to rather than something we shape. The tech bros have decided their version of the future is bunker cities, space colonies, and automation that keeps the human element to a minimum. But their vision is not inevitable. The power of design fiction is in countering these tired narratives with futures that are actually livable, humane, and weird in all the best ways.

Civilization is really just old monkeys creating rules so that new monkeys don’t kill them until the new monkeys finally are old enough to figure it out. But then they’re the old monkeys.

—Rushkoff, SXSW 2025

Rushkoff describes civilization as “old monkeys making rules so that new monkeys don’t kill them.” The problem is, the old monkeys still think they’re in charge. They’ve built systems—economic, technological, political—designed to keep things exactly as they are, while selling us the illusion of progress. Infinite growth. Exponential returns. The same five social media platforms where everything is distilled into bite-sized content for maximum engagement. We’re not moving forward; we’re stuck in a feedback loop of extraction and entertainment.

Design fiction, when done well, disrupts this loop. But disruption itself has been co-opted, sanitized, turned into an industry buzzword. What we need is not more sense-making, more organizing of the chaotic into digestible corporate futures, but more strange-making. More interventions that remind us that the world is not a foregone conclusion. That weirdness isn’t just an aesthetic—it’s a methodology for survival.

Rushkoff talks about how the weird happens in the liminal spaces, the unmeasurable in-betweens. In a way, the act of doing design fiction is about occupying that space. It’s about making a future that isn’t just another extension of our current trajectory but a true divergence. A future where mutual aid isn’t just a survival mechanism but a foundational principle. A future where we don’t solve problems by moving to Mars but by changing the way we exist together here on Earth.

The weirds have always been the ones to create the new stories, the new myths, the new worlds. Not because they were asked to, but because they couldn’t help it. And maybe, just maybe, embracing the apocalypse—acknowledging that the old world is crumbling—frees us to start designing the new one, not by making sense of it, but by making it strange enough to see new possibilities.

Stay weird.

The weirds refers to those on the cultural, intellectual, and creative fringes—people who resist mainstream homogenization and generate new ideas, rituals, and ways of being. They exist at the edges of dominant systems, introducing novelty, discomfort, and transformation, often challenging conventional wisdom and disrupting established norms.

"The mistake many make when thinking about the future is assuming it’s something we must adapt to rather than something we shape."

This line deserves to be repeated.

Thanks for this reminder to be in the liminal spaces. Between the inhale and the exhale.