The Bubble Episode: Part I (Essay)

How Immersive Storytelling and AI Can Slip into the Stream

This post is a collab with Director, Taryn O’Neill, a fellow Near Future Laboratory lab rat. She mentions this post among many other interesting ideas in her weekly Future Film Friday newsletter.

Virtual reality is still waiting for its moment.

The hardware has improved. The headsets are getting lighter. The platforms are smarter. But for most people, VR1 remains a curiosity—something for gamers, early adopters, or tech demos. The problem isn’t the tech anymore. It’s the content. Or more specifically: it’s the lack of a familiar, compelling reason to try it.

Enter the bubble episode.

In traditional television, a bottle episode is a story told with limited characters, sets, and locations—often confined to a single room. These episodes were originally budget-saving maneuvers, but often became creative high points. Constraint, it turns out, is fertile ground for innovation.

A bubble episode brings that same ethos into the immersive age. One room. One story. But this time, the viewer doesn’t just watch—they enter. It’s not just a show anymore. It’s a space. A presence. A standalone experience designed to live within a series, but unfold around you.

It’s not a full leap into the metaverse. It’s a carefully timed step through the screen.

And that distinction changes everything.

From Gimmick to Gateway

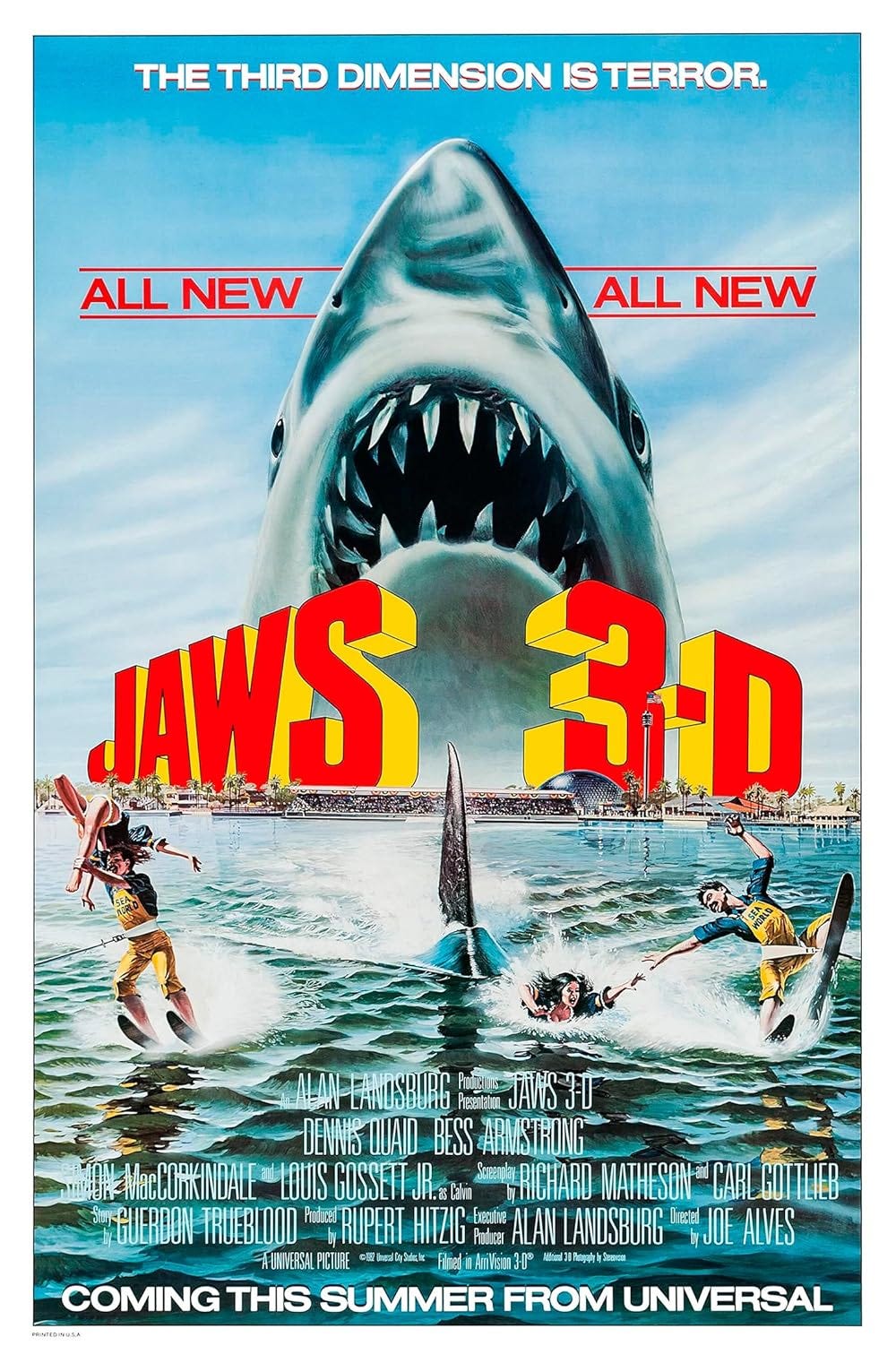

TV has always flirted with technology to shake things up. In 1982, there were the 3D television broadcasts of Gorilla at Large (1954) & Revenge of the Creature (1955), which had viewers rushing to the 7-11 to pick up red and cyan anaglyph glasses. Jaws 3D leaned into the same effect in theaters. More recently, Black Mirror: Bandersnatch gave audiences control of the narrative itself, letting them choose how the story unfolds. And Adolescence, a recent breakout series, shot every episode in a single unbroken take—a bold stylistic constraint that became part of the show’s identity and buzz.

These experiments weren’t always perfect, but they were memorable. They created events—moments where audiences felt like they were participating in something bigger than the usual episode. A brief rupture in the regular cadence of TV.

The bubble episode continues this tradition—but with something more substantive to offer. Unlike past gimmicks, VR doesn’t just make the story look different. It makes the experience feel different. And crucially, it can deepen the relationship between viewer and world.

Lean Back, Look Around

Most TV is a lean-back experience. You press play, sit down, and let the story wash over you. VR, by contrast, has traditionally asked for more—a lean-forward stance that demands constant attention, movement, and interaction. It’s one reason the format has remained niche: it can feel like work.

The bubble episode offers a middle ground.

It’s still a story, not a game. But unlike traditional episodes, you’re inside the scene. You can sit back and absorb the atmosphere, noticing things in your own time. And just when your attention begins to drift, the format gently nudges you—offering brief moments of interaction. A glance. A decision. A question. A shift in focus.

Think of it as the inverse of a video game. Games are mostly interactive, punctuated by passive cut scenes that deliver exposition or deepen character. A bubble episode flips that. It’s mostly passive immersion—long stretches of atmospheric presence—interrupted by short, purposeful interactive beats that invite light agency.

These interactive moments don’t ask much: make a choice, observe a detail, touch an object. They’re not about winning or branching the story. They’re about presence—a subtle way to say: “You’re here, and your attention matters.”

This rhythmic interplay—lean back, lean in, lean back again—could be the missing piece. Just as traditional television relied on the cadence of commercial breaks to re-engage audiences, bubble episodes can use interactive beats as moments to reset, refresh, and reward awareness.

It builds a new kind of attention span—one that flows between watching and participating without breaking the spell.

The Collective Pause

Streaming changed everything. Appointment viewing gave way to binge culture. Seasons dropped all at once, consumed in isolation. The cultural moment disappeared.

But recently, shows like Severance and The White Lotus have nudged things back. Weekly drops. Viewer anticipation. TikTok theories. The water cooler came back—just digital.

What if the bubble episode could augment this return to shared moments?

Picture this: a series drops all at once… except for one special episode. The bubble episode. It’s the penultimate chapter—announced in advance, released on a fixed date. Maybe even accessible early at a pop-up store or via a headset rental program. Suddenly, a binge-watched show has a live, appointment-based moment. A collective pause before the finale. A new ritual for the streaming age.

Severance, with its themes of presence, identity, and workplace unreality, feels particularly well-suited to this kind of immersive treatment. A companion post, a speculative exploration on how that might play out can be found at DesignFictionDaily.com.

The Grammar of the Bubble

VR storytelling is still young. The medium has tropes, but not yet a grammar. Most immersive experiences share a few familiar traits:

A single, constrained location

A limited or silent protagonist

Short runtimes (5–15 minutes)

Passive, first-person presence

A focus on atmosphere over plot

These constraints aren’t arbitrary—they’re shaped by the medium’s limits. Fast camera movement can lead to nausea. Sudden cuts or teleportation between scenes feel disorienting. In most cases, the “camera” is the viewer’s head, so movement has to be motivated—justified by the story, the space, or the presence of a character.

That’s why many effective VR stories embrace stillness and continuity. Consider Submerged, Apple’s immersive short film set entirely inside a sinking submarine. The confined space justifies the lack of camera movement. The tension builds from the environment itself. You’re trapped. You’re watching. The world shifts around you, but you remain anchored in place. It’s like a bottle episode, reimagined for a headset.

This is where the bubble episode thrives. Because it’s rooted in a traditional series, it doesn’t need to explain its universe—it inherits it. And because it happens in a single, grounded location, it sidesteps the nausea-inducing pitfalls of virtual locomotion. There’s no need for constant action. Presence becomes the point.

And from that starting point, the episode can play—with duration, sound, rhythm, proximity. It can experiment with pacing and attention. It doesn’t feel like a tutorial. It feels like part of the show—but it teaches new rules along the way.

Just as classic bottle episodes—like Breaking Bad’s “Fly” or Friends’ “The One Where No One’s Ready”—used limitation to distill character and sharpen tension, the bubble episode uses immersive constraint to deepen presence. The viewer becomes less of a spectator and more of a ghost in the room.

It’s not about giving them control. It’s about giving them context.

Why It’s Hard (And Why It’s Worth It)

Bubble episodes come with real production challenges. They require a hybrid approach—immersive specialists working alongside traditional crews, designers rethinking set layouts to support close-up scrutiny, and writers building stories that can tolerate a slower, observational rhythm without relying on constant cuts or action.

Standard cinematic techniques don’t always translate well to VR. Quick edits can feel jarring. Moving cameras, if unmotivated, risk disorienting or even nauseating the viewer. Instead, transitions must be fluid, anchored in natural shifts in attention or environmental cues. And since the viewer becomes the lens, everything placed within their field of view has the potential to carry meaning—or distract.

While many VR experiences have leaned into 360-degree formats, there’s a growing argument for a more focused 180-degree approach in narrative work. With stereoscopic 180°, viewers can remain in a seated, forward-facing position while still feeling fully immersed. It reduces the need for constant head-turning, prevents surprises from outside the field of view, and respects the natural posture of passive storytelling. Emerging tools like the Blackmagic URSA Cine Immersive camera are beginning to reflect this shift—prioritizing depth and fidelity in a more controlled frame.

Despite these technical and creative complexities, the payoff is significant. Bubble episodes offer more than just a new way to tell stories—they offer a gateway. For viewers, they’re a low-barrier entry point into immersive media: short, standalone, and embedded within a familiar show. For platforms, they create a reason to experiment. And for hardware makers, they provide a format with mass-market potential—one that doesn’t require rethinking entertainment entirely, just reframing it.

Done well, bubble episodes don’t just show off what VR can do. They show where it belongs.

Rewatch, Reframe, Reimagine (With a Little Help from AI)

And once inside—viewers will return. Not because they have to. But because they want to see what they missed.

AI adds a layer of personalization that makes repeat viewing worthwhile. One person might see a different item on the table. Another hears a different whispered line. The core story remains the same, but the details shift—just enough to spark curiosity, discussion, and second viewings. Like Sleep No More in VR, your perspective is never quite the same twice.

That’s where the watercooler talk gets interesting.

The Bubble, Ready to Pop

The bottle episode stripped TV down. The bubble episode opens it up.

It’s immersive. It’s personal. It’s limited. It’s infinite.

And it might just be the next big shift in how we experience story.

Before you go

A companion post, a speculative exploration on how that might play out can be found at DesignFictionDaily.com.

For the sake of brevity, I use VR as shorthand for VR, AR, MR and XR. The bubble episode concept applies to all forms of mixed reality.

Great read, I was thoroughly immersed 🥽

On the subject of VR x AI, I feel like you’d enjoy the new Black Mirror episode Hotel Reverie